|

240-Minute Man

Gabe Sinclair Has Seen the Future, and It Includes

a Four-Hour Workday

By Michael Anft We work

too much.

"I heard on the radio the other day that our

productivity had gone up 4 percent," Sinclair says. "I hear

that and think, Why aren't I working 4 percent less?"

Photo By Michelle

Gienow

| We are what we do. And we do

it more often now than we did 50 years ago. We do it more often even

though it takes us half the time and energy to produce things as it

did then. We do it even THAT we recognize the toll it takes on

health, family, sanity.

Despite a supercharged economy and its formerly middle-class

millionaires, we still do it, ignorant of the predictions of

futurists and technological utopians who once foresaw such a period

of prosperity as entrée to a "leisure society" in which work would

become secondary to the pursuit of filling our ample free time.

That dreamy scenario bit the dust as bytes sped up life (and

didn't make it easier, as technophiles predicted) and the

marketplace overflowed with stuff we didn't really need but bought

anyway. Labor experts say the average U.S. worker put in 80 more

hours in 1999 than in 1979. The problem is even more pronounced for

married working couples with kids, whose collectively put in seven

more weeks a year in 1999 than they did 10 years earlier.

Like manageable work hours, the visionaries and agitators behind

our leisurely future disappeared too. A few academics (former Labor

Secretary Robert Reich, economist/alarmist Jeremy Rifkin) have taken

weak stabs at the ballooning workday, but they're drowned out by

go-go work-is-life management theorists. The labor movement is more

focused on making sure those longer hours are put in by union

workers. The traditional political benefactor of working folks, the

Democratic Party . . . well, enough said. And nary an optimistic

futurist can be found who will say, "You've worked hard enough and

now you're super-productive. It'll soon be time for your reward: A

shorter workweek!"

So, who will step into this void and lead us to a shorter day of

toil? Who will deign to rescue us from our frenzied workweek and the

fraying lives it can cause?

A state-employed machinist from Towson, that's who.

Gabe Sinclair believes he's the man who can lead us back to labor

Eden--or halfway back, at least. With The Four-Hour Day, a

book he self-published in December, and his foundation of the same

name, he aims to kick-start the moribund American trend of making

work hours fit the productivity rate rather than the whims of

profit-addicted managers or workaholics with a fetish for consumer

goods and a matching stomach for credit-card debt.

"People just accept 30 years of eight-hour days with no question

at all," the 51-year-old Sinclair says. "I heard on the radio the

other day that our productivity had gone up 4 percent. I hear that

and think, Why aren't I working 4 percent less? Part of

publishing the book is the notion that we should have a measure of

our prosperity [besides wealth], which would be working less. Right

now, there is no measure."

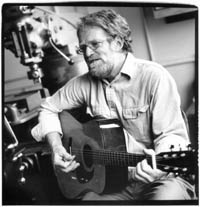

Like think-tank types Reich and Rifkin, Sinclair speaks the

language of labor rollback, but he has the added advantage of

authenticity. With an old sweatshirt, blue Dockers, and a bearded,

bespectacled, weathered face that manages to be both pinched and

friendly at the same time, he oozes proletarian vérité. His own

workday backs up the anti-style: Sinclair makes "gadgets that aren't

commercially available" for researchers at the University of

Maryland Medical Systems, as he has for the past 19 years.

His machine shop, isolated deep in the bowels of the hospital's

Greene Street complex, looks like something out of a '60s

tool-and-die operation. Ancient saws, presses, fans, and desks take

up the visual space, along with the contrasting modernity of a

Mapplethorpe female nude. Sinclair works alone here, concocting

gizmos not far from a room where research animals await their fate.

For visitors, Sinclair might infuse the blue-collar aura with a song

or two, strummed on the six-string Sigma acoustic he keeps under a

workbench. He's written 15 songs that deal with the four-hour day,

ditties such as "Compensation," "Ride for Free," and "Slow Down."

Not that he's overly proud. "I never could sing," he says, before

launching his raspy baritone into another of his versions of the

workingman's blues.

With a book, a foundation, and a set list all lined up, Sinclair

would seem to be well on his way to selling an idea that can't help

but be popular among the overworked and underappreciated. But he's a

man who understands his limitations. "I'm not any good at this," he

says, referring to his lack of marketing skills. And given certain

tenets of his four-hour-day philosophy, he probably needs to

be good at it. Some of Sinclair's ideas--the half day with a full

day's pay, free distribution of life's necessities--you'll probably

buy. Others--female-dominated leadership--half of you might go for.

Still others--eliminating "nonproductive" jobs such as retail

positions and curbing our consumeristic tendencies by not producing

addictive substances such as liquor and cigarettes--might take more

than a quick conversion. And let's not even talk about how

Sinclair's theories on nonviolence fit into all this.

Not yet, anyway.

Indeed, parts of The Four-Hour Day--a proletarian,

futuristic novel/polemic with politics sometimes redolent of

patchouli and hemp--originate way beyond the pale. But we take our

heroes where we can find them. And in the good-humored,

self-effacing Sinclair, we may have the genuine article: a working

stiff for working stiffs, a guy who'll sing protest songs à la Billy

Bragg, a rabble rouser who stopped rousing rabble years ago when he

realized he was being duped but whose ardor has been reborn.

And he wants us to work less.

But to get to his idea of a shorter workday, we have to take a

trip into the hardly workaday mind of Gabe Sinclair.

"I have seen the future, and it works."--Lincoln

Steffens

"I have seen the future, and it works less than we do."--Gabe

Sinclair

If it's true that every great movement starts with a single

footstep, then Sinclair's the one wearing the boots. And we do mean

"single."

"Right now, this is precisely a movement of one," Sinclair says.

"Still, whenever I have a board meeting, fistfights break out."

He has had a little bit of help. Work buddies kicked in $300

toward printing 1,000 copies of The Four-Hour Day, for which

Sinclair put up $4,000. About 100 copies are "floating around" town,

he says; the other 900 or so sit in boxes at his Towson home, under

his daughter's bed. They're awaiting a marketing strategy that's

still in the works but which at the moment includes opinion pieces

so far rejected by national leftist magazines and as-yet-unconfirmed

singing gigs in Fells Point. Sinclair also plans to attend book

fairs, although he worries about being pegged as "a sideshow freak."

The idea for the book might have been formed back in Sinclair's

1960s teenhood in suburban Northern Virginia, when he read "crappy

utopian novels" such as behavioral psychologist B.F. Skinner's

Walden Two and Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward.

"Skinner mentioned the prospect of a four-hour workday. It kind of

stuck with me," Sinclair says. The rest of his upbringing was

depressingly "normal" and middle-class, he says as he reminisces

about his days as a sweater-wearing "collegiate" kid: "My [high]

school was so WASPish. I can't remember any protests or drugs or

long hair on campus," he says. Despite that, young Sinclair

developed a passion for folk music (Joan Baez, Ian and Sylvia) and

futuristic lit (Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, Ray

Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451).

During his senior year, and without much guidance from his

parents or teachers, Sinclair targeted three prospective colleges.

"I picked three schools whose names I thought were pretty cool," he

says. "I had no idea." He eventually settled for the coolest name,

Antioch College in Ohio, where, he decided, he would major in

philosophy. The year was 1967. In preparation for his trip to the

Midwest, Sinclair spiffed up. "Looking nice in the stupid suburbs

meant going to the barber and saying, 'Make me look nice.' I got a

haircut."

When he arrived, Sinclair had an experience that mirrored one of

those bad '60s movies in which the world turns psychedelic colors as

soon as the protagonist enters the counterculture--although at the

time Sinclair had no idea what to make of it. "Culture shock doesn't

begin to describe it," he says. "There was hair everywhere, tie-dyed

T-shirts. Every other stereo in the place was playing Jefferson

Airplane's Surrealistic Pillow. Weird." Sinclair never really

got deeply into his philosophy studies, nor did he buy into the wave

of trendy Eastern religions sweeping the campus . But he did take to

one of the student body's regular pastimes: protesting. "We would

pile into someone's car and drive all night to Washington to protest

the [Vietnam] war," he recalls. "It was exhilarating, even though

I'm not a bullhorn guy." His life as a political rebel was soon in

full kick.

Sinclair spent the supercharged summer of 1969 working with

emotionally disturbed kids in "a Northern Californian paradise."

Even though he had been asked to stay on full time, he left, feeling

obligated to go back to school. He says now he probably shouldn't

have. "It [was] impossible to get back into [German philosopher

Georg] Hegel after that. I stopped going to classes. I played a lot

of volleyball."

By January 1970, Sinclair was finished with Antioch. On the

recommendation of a friend, he headed back east to visit the Twin

Oaks commune in central Virginia. He liked the place's tranquility

and agrarian/socialist politics, and he decided to stay. "It wasn't

exactly a beehive of activity," he recalls. But the commune, which

still exists, did provide him with a conversion experience--if not

the kind he expected. During a plumbing crisis, Sinclair--to the

astonishment of his lethargic fellow commune dwellers--grabbed a

propane torch and a hacksaw and fixed a pipe leading to the toilet.

"I learned I could work with my hands," he says.

But that's about all Sinclair got out of his Twin Oaks

experience, he says--that and his first taste of media coverage. "We

were hot news for a while there," he says. "Reporters would come

every weekend to report on these hippies living in the wild, blah

blah. But that petered out." As did his passion for the place: "We

were attracting disaffected middle-class folks with problems. We

weren't exactly a kibbutz."

Sinclair left the commune in 1974 and began working for an

offshoot of the once-considered-radical Students for a Democratic

Society (SDS), specifically its labor committee, which later

metamorphosed into the U.S. Labor Party. Its leader: Lyndon

LaRouche. For reasons most of us can understand, Sinclair remains a

bit embarrassed about his days stumping for someone many consider to

be a dangerous charlatan. "The guy was a complete jerk," Sinclair

says. "He went from the far left to the far right in the five years

I worked for him. I learned from him that violence doesn't have to

be physical. Humiliation can be violent too."

Sinclair moved to Baltimore in 1976, where he shared a house with

another LaRouche worker named Nancy. By day, Sinclair worked as a

machinist in Laurel; at night, he and Nancy sold copies of the party

organ New Solidarity, going door-to-door six nights a week

and soliciting donations, then meeting the late shift as it left

Bethlehem Steel at 11 p.m. to attempt more sales. At midnight, they

turned over whatever cash they'd collected to the LaRouche

hierarchy. "We sold pamphlets with pink covers that said things like

'What Only Communists Know About Lyndon LaRouche,'" Sinclair

recalls. "Ever try selling stuff like that in Edmondson Village?"

They battled Moonies over corners ("They were tough"), and at least

once Sinclair guarded the door of LaRouche's hotel room. "There was

a helluva party going on in there," he remembers. "I walked in

afterwards, saw wine bottles everywhere, and said to myself, 'This

is where all my money is going!'"

By 1978, when LaRouche was touting Alexander Hamilton as more

revolutionary than Karl Marx, Sinclair was exhausted but didn't know

how to escape. The psychology of the group was to make members feel

worthless so they'd believe they would be nothing outside it, he

says. "That was what kept the whole thing going," he says. By then,

he and Nancy had found more than economic reasons to be together.

When Nancy told Sinclair she wanted a baby, "I took that as code

for, 'Let's get out of here.' We credit our daughter Melissa with

saving us." And just in time: Shortly afterward, some LaRouche

followers were indicted for predatory phone solicitations during

which they'd tapped the credit cards of the unwary and elderly.

Although those years were clearly harrowing for Sinclair and his

wife, now a teacher at a Baltimore County high school, he says they

did teach him a lesson of sorts. "It's tempting to say I wasted five

years working for LaRouche," Sinclair says. "But when your idealism

leads you into a cult, you'd better do some serious

self-examination." The result was a decision to put his activist

impulse on hold and raise his family, which also includes two sons.

He accepted a job with the University of Maryland in 1982, worked on

an unsold novel about a female arm-wrestler with a penchant for

political organizing ("I picked the most preposterous thing I

could," Sinclair says. "I had no idea there were women who

arm-wrestled."), and honed his ideas about the way Americans work

and consume. By all accounts, his life on a quiet street in Towson

had become tame, even--dare he admit it to his mostly Republican

neighbors--respectable.

His response was to return to writing. Awakening many a morning

at 5, before his eight-hour day began, Sinclair sat over coffee and

Cranberry Almond Crunch cereal at his daughter's computer (she's

away at college), channeling his accumulated knowledge and

experiences into a new book, adding some strange fictional twists

along the way. Despite his queasiness over Skinner's and Bellamy's

visions of a perfect tomorrow, much of The Four-Hour Day is

set in a utopia called Aurora, which Sinclair locates in the Jones

Falls Valley. There, the time-traveling character "Gabe" falls for

an Earth-mother type named Avien who, like other Aurorans, speaks in

pidginlike blank verse. Aurorans don't drink, smoke, or spend time

at X-rated theaters. "But I don't want the whole thing to appear

puritanical," the author says. True enough, there are unisex baths

and something approaching free love.

And there's the four-hour day, based on a "producerist" economy

that highlights creativity. Sinclair adds in a few neo-Luddite

touches--Avien weaves, and other Aurorans do craft-y things. Not

that he touts some return-to-the-land, back-to-basics nostalgia as

The Answer. He merely offers it as one possible, way-in-the-future

solution to our economy, two-thirds of which is driven by consumers.

To get there today, he proposes moving 36 million service-industry

workers and 19 million managers--about 42 percent of the total U.S.

work force of 132 million--into manufacturing jobs. Despite the

trend of corporations moving factory jobs overseas to take advantage

of cheaper nonunion labor, Sinclair contends that people who work

with their hands are generally less fearful about their professional

prospects than white-collar folks. "As a machinist, I know I can go

anywhere and get a job," he says. "My father was an insurance

salesman. He was a very nervous man."

Since everything in Sinclair's utopia is given away, there is no

profit motive. Greed has become passé. Waitresses are as likely to

lead as anyone, tapping into "the relaxed, nonviolent authority

women use to run things." People make things--including the usual

necessities such as steel and vehicles--but because so many of them

make things people actually need (and not, say, Game Boys or Pabst

Blue Ribbon), they only have to work four-hour days. Since people

will presumably be happier with this new work arrangement, various

addictions, including conspicuous consumption, will disappear, as

will the need to pay for curing them. With extra free time, people

will "reconnect," take care of their communities' needs, and get

involved in daily local politics. They won't, presumably, become

hooked on soap operas.

"[S]o long as there is one man who seeks employment and

cannot obtain it, the hours of work are too long."--American

Federation of Labor President Samuel Gompers, 1887

As New Age-y as Sinclair's ideas may seem, they are part of a

long tradition. In the United States, progressive movements and the

enterprising politicians backed by them were fighting for shorter

workdays as far back as the 1830s, when a six-day work week and

12-hour days were common.

Mid-19th-century supporters of a reduced workday offered a number

of rationales. Artisans and mechanics in Baltimore, Boston, and

Philadelphia who pushed for a 10-hour day cited their own

perfectibility as healthy, educable citizens as one reason.

Employers predictably hated the idea, saying shorter days would lead

to "idleness and debauchery." Nevertheless, by 1840 those workers

had won a two-hour daily reduction. President Martin Van Buren

bought into the idea and issued an executive order establishing a

10-hour day for people working on federal projects. But such

victories were few; the 12-hour day prevailed throughout most of the

country until after the Civil War.

In 1866, a group of unionists held a convention in Baltimore

where 77 delegates from around the country formed what would later

be called the National Labor Union. They backed an eight-hour day,

which they said would raise the social and economic status of

workers. Some strikes over the next few decades garnered public

support for the idea, although there were setbacks such as the

Haymarket riot of 1886 in Chicago, during which one policeman was

killed (and after which four labor organizers were hanged). Toward

the end of the century, labor leaders such as American Federation of

Labor President Samuel Gompers began to tap into the concept of full

employment, arguing that the unemployed could take up the slack

hours from workers who toiled fewer of them. (Congress of Industrial

Organizations President Walter Reuther took up the baton in 1961,

calling for shorter hours to guarantee jobs for every able-bodied

American. Jeremy Rifkin, in 1995's The End of Work, heralded

the idea, citing the likelihood that most jobs would be taken by

machines.) The high-water mark of the movement came with the passage

of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which institutionalized the

eight-hour daily shift, but few have pushed for going beyond that,

And that has remained the standard, with a bit of backsliding in

recent years. In 1969, the average working American toiled 40 hours

a week. Over the next 20 years, that rose another three-plus

hours--the equivalent of an extra four weeks at the office or

assembly line over the course of a year. Things may have improved in

some sectors of the flush 1990s economy: Numbers from January

compiled by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics show that

goods-producing workers in private industry were working 40.4 hours

per week.

"If I told a lot of people they could work a

four-hour day, I'd scare them." —Gabe Sinclair

Photo By Michelle

Gienow

| But few have pushed to go

below 40. The AFL advanced a proposal for a 30-hour workweek in 1937

to combat a Depression-era unemployment rate that would go as high

as 25 percent. Two decades later, AFL-CIO President George Meany

talked of reducing the week to 35 hours, to no avail. As Harvard

economics professor Juliet B. Schor noted in her 1991 book The

Overworked American, leaps in worker productivity did little to

help workers gain free time, although incomes in many industries

sharply increased. Given the doubling in productivity from 1948 to

1991, she wrote, "every worker in the United States could now be

taking every other year off from work--with pay. . . . But between

1948 and the present we did not use any of the productivity dividend

to reduce hours."

Like Gompers, Reuther, and, later, Rifkin, Schor thought this a

travesty given the nation's relatively high unemployment rate at the

time. The End of Work, Rifkin's 1995 death knell for labor,

added a computer-age twist to the argument, warning that industry

would have to restructure the workweek to make room for laborers who

were displaced by advancing technology. But both Rifkin and Schor

missed the boat, at least for now: With the official unemployment

rate hovering around 4 percent, making room for those without work

has more or less become a moot point. And in what must seem a huge

blow to labor organizers, many workers seem to want to spend long

hours on the job, either out of fear of losing their jobs or because

they enjoy it, say Reich and others.

These days, the notion of shortening the workweek registers

barely a blip on organized labor's radar. Ernest Grecco, president

of the Baltimore Metropolitan Council of AFL-CIO Unions, says some

unions have negotiated for fewer hours, "but there's no real effort

to lower hours across the board. The labor movement has advocated

for flex time, longer vacations, and allowing more time for

employees to spend with their families. [Mandating fewer workday

hours] is not one of our priorities."

"The United States is not ready for the four-hour day."

--Gabe Sinclair

Given the zeitgeist, Sinclair knows it'll take a little

time--perhaps millennia--to make the four-hour day happen. Leaning

back in a chair in his daughter's room, decorated with fish painted

along the tops of the walls, he can smile about that. Sure, cutting

everyone's workday back is a great idea, he says, one overworked

folks everywhere who are struggling to balance leisure, family, and

jobs should think about. But people aren't ready to give up their

creature comforts, the monkeys on their backs. In Sinclair's world,

with its free distribution system, some might worry that others are

hoarding all the goodies. The Gandhi-style nonviolence that

underpins his vision can't be taught in a generation. And there are

those workaholics to deal with. "If I told a lot of people they

could work a four-hour day, I'd scare them," he says. "For a lot of

them, work is the only social life they have. They wouldn't know

what to do with four extra hours."

These things take time. There are only so many hours in a day.

Sinclair's willing to admit he's not going to sweep the country

by storm. He's determined to lay the foundation one hand-carved

stone at a time.

"I will be extremely happy if one in 10,000 Americans responds to

this," he says, outlining his outreach plan. "That would be 27,000

total. Can you imagine what we could do with 27,000 committed,

like-minded people?" He's convinced these like-minded people will

hold their first four-hour-day convention in a few years. If any of

them--especially one who is an "unscrupulous marketing genius"--want

to appropriate his ideas as their own, fine. He didn't copyright the

book--he doesn't even charge an official cover price, asking instead

for a $15 tax-deductible gift to his foundation--so people would

feel free to run with the idea.

Not that he won't stump on his own. He'll still meet with women's-movement

leaders, he says, because "women are a lot less psychotic about

work than men are." He has high hopes for a partnership with the

Green Party. He wants to see what labor leaders have to say. He'll

keep his Web site (http://www.fourhourday.org/) fresh, and he's still

sending opinion articles to progressive publications, now with

notes that read, "I reject your rejection." He'll continue to

hone his guitar chops for gigs at coffeehouses and bookstores

that haven't been booked yet. He's just a man with an idea, he

says, one he feels compelled to share. "All I want to say with

the book is that the four-hour day is thinkable," he says.

He'll even make an example of himself, putting his security on

the line in service of the cause, Sinclair says. He'll gleefully and

unilaterally cut his eight-hour shift at the machine shop in half.

But not just yet.

"Maybe when I get my last two kids through college," Sinclair

says, looking a little sheepish. And there's really no reason to

hurry. Rome, like social movements, wasn't built in one workday.

|